The Cannoneer: Recollections of Service in the Army of the Potomac, Augustus Buell, (Wash 1890)

p. 148 commenting on how Battery D (Griffin’s battery) “was a very safe place to be in.” From spring ’62 to spring ’64, it had lost 38 men

p 149: officers who had been promoted up from Battery D: Griffin, Alex Webb, Adelbert Ames

p. 150 : armament of V Corps batteries

p 157 : At Wilderness, Griffin’s 1st Division had Martin’s 3D and Phillips’s 5MA, and Winslow’s batteries

p. 162 Loss of Winslow’s guns taken by Doles’ Brigade, Rodes’s Division 5/5/64– blamed on Ayres’ withdrawal

p. 163 first and only guns lost by V Corps – retaken by 8NYCav in rout of Early at Cedar Creek 10/29/64

p. 209. 6/2/64. -Bethesda Church: “Suddenly Gen. Griffin beckoned to Stewart, who left us and rode over toward the General. But, divining what Griffin wanted, he said, as he wheeled his horse round : “This means us, boys. Drivers, mount! Cannoneers, mount! Attention!” A few words passed between the General and Stewart, which I did not hear, of course, being at that moment in the act of mounting the limber-chest, but afterward learned that Gen. Griffin said: “James (he usually called Stewart by his first name in that way), can you go in battery under that fire?”

“Yes, sir; where shall I unlimber?”

“Suit yourself about that, but keep an eye to your supports. I would like to see that battery silenced.”

“I will shut it up, sir.”

Now, this question as to whether we should unlimber on this side or [210] the other side of the low ground spoken of was a very important one. If we unlimbered on this side (that is, the side near the church,) we would have over half a mile range, and would have to fire over Bartlett’s head — or, rather, over his men. But if we crossed it, we would have to go in battery within a few hundred feet— feet, mind you, not yards — from the enemy’s muzzles, and that was right on Bartlett’s skirmish line ; in fact, a little beyond it, becanse Bartlett’s skirmishers were taking cover of the slight bank formed by the descent from the high ground. Having his choice, as before stated, the Old Man chose the close quarters! Every man and boy in the Battery saw instantly that this was the finest opportunity of the campaign to show the stuff we were made of. There was, as re- marked in a former chapter of this sketch, a strong feeling of rivalry between our Battery and Rittenhouse’s, which was Griffin’s old battery, and Griffin had an enormous amount of conceit about his old battery. So we all had the same thought that this would be a fine opportunity to take that conceit out of Gen. Griffin, and to show him what “Gibbon’s old battery” could do.

Turning from Gen. Griffin, Stewart whipped out his saber and spurred to the front of the Battery column, executing a “right moulinet” as he did SO. “Attention — forward, march! Trot!!- Gallop !!!” And then, as the huge wheels began to thunder behind him and the tramp of the power- ful horses and the yells of the drivers and cracking of the whips mingled with the “swish, swish” of the enemy’s canister down the pike, he bent forward over his horse’s neck, and spurring him to a run roared out like a lion: “Come on, boys! Follow me!!- Charge !!!” This was an order not included in the “Light Artillery Manual,” but we all knew what it meant. And to this day the surviving veterans of the Fifth Corps will tell you about the “Charge of Stewart’s Battery at Bethesda Church!”

p. 214. When the enemy deserted his guns and left them standing silent in the field near the pike, and his infantry recoiled into the woods, it appeared that we had practically captured a battery from the enemy! About this time Gens. Griffin, Bartlett and Ayres came up into the road where we were, and Griffin suggested that as we had silenced the enemy’s battery, and it was too late to make an infantry advance, we might as well limber up and go back to the church.

Stewart asked Gen. Griffin if he was not going to advance his infantry to take in the enemy’s deserted guns. He said no, because that would in- volve too close an approach to the enemy’s cover in the woods, which they were clearly holding in force. Then the Old Man said, “if you will ad- vance your skirmish line to cover me, by — I will take some of my teams and haul them in myself with my men !” Stewart was very anxious to get those guns. Of course it would have been a very desperate thing to go out there and haul them in, covered as they were by all of Rodes’s infantry in the edge of the woods on the north side of the Mechanicsville Pike, but he would have done it if he could have got the necessary support. We had destroyed nearly every man and horse they had. They were waiting for darkness, so as to haul their dismantled guns off by band. We had lost only 14 men and not more than a dozen horses. We felt that we had really captured their battery, because we had destroyed every living thing in it, and had made it impossible for anyone to approach the deserted guns. But we could not go out and hook on to the guns and fetch them in without the support of a general advance of our infantry. This Gen. Griffin would not undertake; so, after dark, they hauled their dismantled guns off by hand. No doubt Griffin was right. He always was. It would have cost some lives to go out and get the Rebel guns which we had dismantled, but there was not a man in the Battery who would not have jumped at the chance to volunteer with the teams to go and fetch them in. As it was, whenever the enemy’s infantry showed up in the edge of the woods from that time till pitch dark, we soon sent them to the right about with a few rounds of case and canister. They kept sharpshooting at us till dark, but did not hit anybody. Finally, when Gen. Griffin decided to draw in his picket line about 9 o’clock, we limbered up and went back to the field in front of Bethesda Church, where we bivouacked for the night.

Stewart was the only commissioned officer of the Battery present in this affair; as, in fact, he had been ever since May 8.

p.217 (still 6/2/64): “As the Battery was then reporting directly to Gen. Griffin, who acted as his own “Chief of Division Artillery,” and put the Battery into action himself, the report of the action was to be made to him. So, when he rode [218] into the Battery, he told Stewart that he wanted him to make a full report of that action, and to mention all the men who had distinguished themselves. Whereupon the Old Man replied : “In that case, General, I will simply have to append to my report the present for duty roll of the Battery, sir!” After it was all over Gens. Griffin, Bartlett and Ayres came into the Battery and showered congratulations and compliments on Stewart and on the men individually. Griffin and Ayres, being veteran Regular artillerymen, were particularly enthusiastic. Gen. Griffin, noticing a piece of courtplaster on my eyebrow, and that the middle finger on my left hand was done up in a rag (this was from my fight with Paddy Hart’s man two or three nights before, as already stated), said: “I see you have been hit.” I replied: “Oh, sir, that was. in a previous engagement!” This made the boys laugh, but the General thought it was all right, and I did not take the pains to tell him what kind of an “engagement” it was.”

p. 318. I did not go on duty with the Battery after my return, except to do some writing for Mitchell, and Orderly duty when he went anywhere mounted. He said he would have given me a gun if I had been present during the reorganization, but couldn’t do anything for me as it was. However, in a few days he prevailed on Gen. Griffin to give me mounted duty at division headquarters; so the little mouse-colored mare was as- signed to me, and I reported to the headquarters of the First Division.

The enlisted Clerks and Orderlies at these headquarters were a nice lot of boys, but I can’t recall many of them by name. Griffin’s Clerk was Benson, of the 20th Maine. Then there were Hyatt, from Griffin’s Battery, Hall, Russell, Davis and others from different infantry regiments in the division, Orderlies or Clerks, and a squad of the 4th Pennsylvania cavalry as escort.

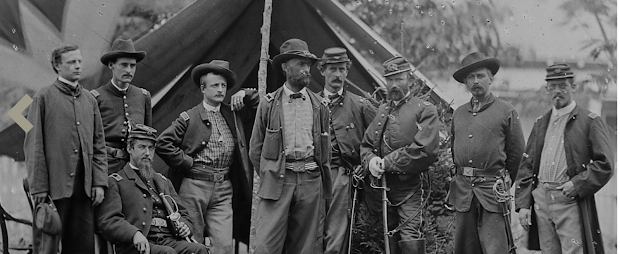

p. 320. “I have always thought that Gen. Charles Griffin does not receive the place in history to which his services and personal character entitle him. Doubtless his untimely death, in 1867, at the age of 40 or 41 years, caused him to pass out of the minds of men in view of the rapid procession of great events and great men, but he certainly won more distinction than has ever been accorded to his name. He served through the whole war, rising from the rank of Lieutenant, commanding Battery D, 5th Regulars, in the battle of First Bull Run, to Major-General, commanding the Fifth Corps at Appomattox Courthouse. As a man he was of gentle and generous disposition, with a keen sense of humor and a disposition to make every one about him enjoy themselves. The hospitality of his mess was proverbial in the army, and the charm of his conversation was something to be remembered. In all the little affairs about headquarters, in which the man shows out through the officer, Griffin was so kind and good and considerate that it was a joy to serve him, even in the humblest capacity. He was a horse fancier, and his stable was among the finest in the army. On one occasion one of Crawford’s Orderlies, a cavalryman, brought him a message requiring a reply. Griffin might just as well have sent the reply by Crawford’s Orderly, but he dismissed him and ordered one of us to sad- dle up. This cavalyman was not in good form, and his horse looked more shabby than he did, if possible. Gen. Griffin remarked in his dry way that he would not send a message by such a scarecrow mounted on such a sheep!

As an officer, Gen. Griffin was always cool, quiet and precise. He never affected the heroic, and in action always stationed himself at the most advantageous point whence to observe the operations of his troops ; he always knew exactly where every one of his brigades, or even regiments, was; his division was always well in hand. You would never see him “sword in hand, leading a forlorn hope,” as the historians like to depict their heroes; and he did not expose himself in battle unless it was absolutely necessary for him to do so in the proper discharge of his duties as division commander. He regarded warfare as his profession, and battle as a business transaction in pursuance thereof. But while very cool, un- demonstrative and methodical himself, he was quick to see, admire and reward gallant or even reckless exposure on the part of his subordinates.

They used to tell about headquarters an anecdote of Gen. Gregory, who had been a minister of the Gospel, and who used generally to be called, in the slang of the Fifth Corps, “The Fighting Parson.” At the Weldon Railroad, or in some of those battles near Globe Tavern or Ream’s Station, Gregory had behaved with unusual bravery, involving most [321] sure. I think he lost two horses. Griffin, though not by any means a “Christian soldier” himself, was fond of Gregory, and had great faith in him as a brigade leader. So when Griffin heard of this affair he said that Gregory had a great advantage over most of the other officers in that the others had to fear both the Rebels and hell, whereas Gregory was in danger only from the Rebels !

Gen. Griffin’s great reliance was on Bartlett, whose brigade he always called the right arm of the division. Besides, their personal relations were very close, and Griffin always consulted Bartlett in even individual mat- ters outside of their field duties. With the exception of Ayres, early in 1864, the brigade commanders, during the time when I knew the division, were all civilian soldiers; and Griffin, though an ardent West Pointer himself, never made any effort to have West Pointers put in command of his brigades, but was perfectly content with Bartlett, Gwyn, Sweitzer, Gregory and Chamberlain.

But there was one situation in which Gen. Griffin would show enthusiasm. That was when he could get a chance to handle two or three bat- teries in a field where that arm could do execution. Then all his old artil- lery instincts came to the front. He used to say that, so far as the satisfaction of the service was concerned, he would rather handle a brigade of six batteries in action than any other possible command. Gen. Griffin used to be profuse in his praise of the volunteer artillery and the old Regular rankers. He often said that West Point had never educated a more accomplished artillerist than James Stewart, who came from the ranks of the Regular Army; or than Charley Phillips, of the 5th Massachusetts ; Charley Mink, of H, 1st New York; or George Winslow or Lester Richardson, of D, 1st New York, and others who came from civil life whose names do not now occur to me.

In his intercourse with other officers, Gen. Griffin was quiet and courteous, though not excessively punctilious, his ruling impulse being to display good nature and make every one feel at his ease in his presence. He would swear sometimes, but as a rule he was not what would be called a man addicted to profanity. Socially he was very hospitable, but drank very moderately himself, even in the festivities of Winter quarters, which sometimes ran pretty high. Intellectually he was not what you would call a brilliant man, but his views were always safe, his judgment always sound, and his perception always acute and accurate. Whether as a Lieutenant commanding Battery D at the First Bull Run, or as Major-General commanding the Fifth Corps in the Appomattox campaign, he was always the same cool, careful, discreet and successful officer. He grew right up with his increased responsibilities, and he would have displayed the same solid, sterling traits had fortune called him to the command of the army. I think that his name will yet find its proper place in our military history.

The brigade commanders of Griffin’s Division at this time were Joseph J. Bartlett, of New York; Edgar M. Gregory, of Pennsylvania, and Cham- berlain, of Maine. Bartlett was the senior Brigadier-General, though his [322] brigade was numbered the Third Brigade of the division. Chamberlain was a professor in Bowdoin College, who had come out as Colonel of the 20th Maine, and had been promoted for gallantry at Gettysburg and elsewhere. Gregory had been a Philadelphia preacher, and had made his debut in the army as Colonel of the 91st Pennsylvania, a most gallant regiment, and one that made a record second to no other. These three men were a curious study to me from day to day in the discharge of my messenger or Orderly duties. Bartlett was the beau ideal of a soldier. On horseback, in full uniform, he was the most perfect picture of the ideal officer that I ever saw. Dealing with officers he was sometimes pretty tart, and occasionally a bit emphatic, but always kind, gentle and comrade-like toward the enlisted men. It was a pleasure to a mounted Orderly to be sent with a message to Gen. Bartlett. He would look at his watch, ask what time we left the division or corps commander with the message, and then say : Report that you delivered this to me at such and such an hour and minute, whatever it might be, which we would always note carefully in our little Orderly books. Chamberlain was a cold, unlovable man, very brave and all that, but not dashing either in appearance or manner. He always reminded me of a professor of mathematics we had in college. Still, he was a gallant officer, and had more than once been desperately wounded while leading his troops in the most deadly assaults.

Gregory was a solemn, serious man, but he always spoke to us in kind, gentle tones, and we all liked him. He was a fighter in battle, but in camp he used to have prayer meetings and all that sort of thing, and I am afraid that the wicked boys about division headquarters used to make ri- bald, and sometimes blasphemous, comments on “Parson Gregory,” whom, despite his kindness to us, we used to call with great irreverence the “Bible- banging Brigadier !”

I must say that among the unregenerate boys about Griffin’s head- quarters, the dashing, handsome and wicked Bartlett was much more ardently admired than the scholarly Chamberlain or the pious Gregory ! And I also fear that candor compels me to add that there was not much religion in the moral atmosphere of Griffin’s headquarters in front of Petersburg.

When Griffin went away on leave about Christmas, 1864, Bartlett took command of the division. At this time Gregory had a number of recruits in his brigade who had enlisted (for large bounties) out of some theological seminary in Western New York. I think they were in the 189th New York, a new regiment. They had a large hospital tent fitted up as a meeting house, and used to hold prayer meetings there. Bartlett thought they ought to have more brigade drill, even at the expense of less psalm singing. So he took Gregory to task about it one day. Not long after Gregory wanted Bartlett to approve details of a lot of men from his brigade as division train teamsters. Upon investigation Bartlett discovered that these men were the theological student recruits before mentioned, whereupon he refused to approve their details, saying that as these men were all ready for Heaven they should be put to the front; and if any men were to be detailed as teamsters [323] hey should be the tough, wicked old fighting veterans who were sure to go to hell if they got killed! I do not know how Gen. Gregory took this rebuff, but so long as Bartlett commanded the division all the details for duty in the rear were made from among the “wicked old veterans,” and the pious recruits had to remain at the front.

Notwithstanding his apparently calm nature, Griffin’s likes and dislikes were very strong. It is not necessary to state whom he disliked. But the men he liked were Hancock, Gibbon, Ayres, Bartlett and particularly his wife’s brother, Gen. Sprigg Carroll, of the Second Corps. He was fond of Getty, Wheaton and Davy Russell, of the Sixth Corps, and also of Gen. Orlando Willcox, of the Ninth Corps. He had also a profound admiration for Gen. Henry Heth, of Lee’s army, who had been his “chum” at West Point, and he used to say that it gave him more satisfaction to drive Heth’s Division than any other command in the Confederate army. I am sorry to say that he did not always have the satisfaction of “driving Heth.”

p. 349 Five Forks. “Advancing according to Gen. Sheridan’s program, Crawford crossed the White Oak Road east of the enemy’s intrenchment, and kept on in the [351] woods, Griffin following, until our division had got perhaps a quarter of a mile north of the White Oak Road. Crawford marched more rapidly than we did, because Griffin, having been ordered by Sheridan to hold himself in readiness to support either Crawford or Ayres, as occasion might require, kept holding his head of column to see what might happen. Following Gen. Griffin through the woods, I could see that he was in doubt and much disturbed in his mind, because, according to program, Crawford should have struck the Rebel angle at the White Oak Road, whereas both divisions had now crossed that road. He slowed the march of his column and sent an Aid up to Gen. Gregory to tell him to halt his brigade, which was leading, and to wheel on his left as a pivot out into the Sydney Farm, and, if the enemy was there, to attack them. At this moment Gen. Griffin was with one of the brigade commanders, either Bartlett or Chamber- lain, and as the division halted he started to say something. He had just begun his sentence when blizzard after blizzard of musketry sounded close in our left rear!

Listening a moment, Griffin said: “Ayres has struck their works ! We have passed their flank !”

By this time the head of the column of Chamberlain’s Brigade had come up, and Griffin halted it. At the same moment an officer – I think it was Col. Newhall, of Sheridan’s staff — reached Griffin with Gen. Sheridan’s compliments and inquired where Crawford was, which Griffin was unable to tell him. Gen Griffin and this officer rode out to the edge of the clearing of the Sydney Farm, where the whole situation flashed upon them. During this time several staff officers from Sheridan — Col. Mike among them —got to Griffin with the news that Ayres had struck the Rebel works, had been checked, and was reforming his division for another assault; that our division was already across the enemy’s rear, and for the sake of — – , as Col. Mike put it, with more eloquence than elegance, to wheel the division into the clearing and “give it to ’em.” Parson Gregory was already out in the Sydney Clearing, and had struck a line of [352] slight breastworks that the enemy had thrown up there to protect his left rear, and his brigade had been checked. Then Gen. Griffin, as soon as he saw this situation, ordered Chamberlain, who was already wheeling to the left, to take the return of the enemy’s work in reverse and connect with Ayres’s right, as it was now plain that we were obliquely in rear of their works, and that, by quickly connecting with Ayres, who was attacking them in front and on their left flank, we could “shut up on them like a jackknife.” Chamberlain, however, saw the situation as well as Griffin did and was in motion already. Gregory’s Brigade appeared to have been slightly checked by the first fire they received, and as Bartlett’s larger brigade was wheeling in two lines of battle on difficult ground it was necessary for it to move deliberately in order to avoid dislocation. Therefore two couriers — Hyatt and myself — were sent to Gregory with the message to hold the ground until Bartlett could reach him. Trying to reach Gregory by a short cut across the enemy’s right front, not more than 200 yards from his skirmishers, Hyatt’s horse was shot under him, so that he had to go back to headquarters on foot, lugging his saddle. Meantime I got to Gen. Gregory, who was at that moment riding along the line of the 188th New York, and delivered the message. It was not necessary, however, as he was doing the same thing of his own motion — waiting to attack in concert with Bartlett. As soon as the Parson saw Bartlett’s front line emerge from the woods he ordered his brigade forward again.

Bartlett had a huge fellow posted as “marker” on the objective flank of his first line, and he stood there with the butt of his musket up in the air just as if this was a review, while the General himself kept in front of the wheeling flank, his horse curvetting in fine style and he marking time with his saber. But you must bear in mind that all this was being done under musketry fire at a range not exceeding 280 or 300 yards from two brigades of the enemy who occupied the reverse works of their line. I wish I had the power to put on canvas the picture that my memory holds of Gen. Joseph J. Bartlett as he wheeled his old brigade into the Sydney Farm at Five Forks, and squared it for its 50th battle, its last charge and its final victory. Having wheeled about they squared up their formation, and then it was, “Forward, right oblique” (as they had to take ground to the right), and then “Quick, march !” “Double quick !!” and “Charge !!!” And with the last order Bartlett spurred to the right of his line, swung his saber and shouted “Come on, now, boys, for God’s sake!!” At this I forgot all about my duties to Gen. Griffin and, being seized with uncontrollable enthusiasm, spurred my little mare along after Bartlett’s big dapple-bay horse, regardless and oblivious of everything except the row that was on hand. I never knew an officer who had such power to inspire men in action or as much magnetism of personal presence as Gen. Bartlett had. I knew that nothing could stop that old brigade then. Meantime the Fighting Parson (Gregory) and his little brigade, which had only men enough for a single line of battle, were ready, and when Bartlett’s con- nected with them the two went over and over and through and through [353] the Rebel reverse works like a cyclone through a Kansas village! Well, the wreck of the two Rebel brigades which were in those works— some of Bushrod Johnson’s Division — was indescribable. I had seen the Rebels driven many times, but never saw them “quit and throw up the sponge” as they did here at Five Forks !! Ordinarily they would either run or re- tire in some kind of order, but here they simply threw down their muskets, threw up their hands and quit!

Then, for the first time, as I jumped my mare over their poor little breastwork of rails and brush, following Bartlett, I began to realize that the end was nigh and that peace was at hand. Somehow I felt sorry for them. I could not help it. Of course I knew they were in the wrong, and that their rebellion against the Government and attempt to divide the Union was a crime; but they had fought so gallantly and suffered so gamely that I couldn’t help feeling sorry for them in this poor little “last ditch” of theirs at Five Forks, when Joe Bartlett and Parson Gregory overwhelmed them for the last time and for eternity. From this time on it was a sort of walking match — “go as you please.” The impetus of the charge had to some extent disordered Bartlett’s and Gregory’s Brigades, and they were all mixed up with the routed and surrendering Rebels ; but the whole mass kept on down toward the White Oak Road, which, generally speaking, was 500 or 600 yards from the reverse works just stormed. Arriving at the White Oak Road, and taking the enemy’s main line in rear, there was a literal pandemonium. Here we found the remnants of Pickett’s Division in a state of wreck that beggars language to describe. Ayres had stormed their works in front, Chamberlain had taken their return intrenchment in rear and reverse, while our dismounted cavalry, vieing with their infantry comrades, had scaled the breastworks in their front near the Forks, and it was hard to tell which was in the greatest disorder, our folks or the Rebels, though it was easy to see which had whipped.

At this moment Gen. Griffin, with some of his staff, was riding up to the road, and I at once joined him. Gen. Griffin asked if I had seen Gen. Gregory. I said, “Yes, sir; he is over there to the right,” (pointing along the White Oak Road to the westward.) Then he dictated a message, which I carried — but do not exactly remember its contents. When I returned Gen. Griffin was surrounded by officers congratulating him, and I soon learned that Gen. Warren had been relieved and that my General now commanded the Fifth Corps.

p. 356: Gen. Humphreys was a very nice, pleasant-mannered man, as well as a most accomplished officer. He proceeded to write a brief note to Gen. Griffin, and hearing him call up one of his couriers and begin to tell him how to reach Griffin’s headquarters I stepped toward him, with my tincup in one hand and a hardtack in the other, and said : “Beg pardon, General ; but I can carry any dispatch you may want to send to Gen. Griffin.”

“Do you expect to return to-night?”’ asked the General, elevating his eyebrows.

“Certainly, sir. I had no orders to do anything else.”

So Gen. Humphreys sent his own courier back to his bivouac and handed me the message to Gen. Griffin.

I have since learned on reliable authority that the message which I carried that night from Griffin to Humphreys was an unofficial or private one as between gentlemen, stating the circumstances of the relief of Warren and his (Griffin’s) assignment to command the Fifth Corps, and assuring him (Humphreys) that he (Griffin) had not the slightest share in or re- sponsibility for the transaction, officially or personally ; that, while accept- ing the command and striving his best to accomplish results, he regretted keenly that such action should have been deemed proper, and that, under the circumstances, he assumed command of the Fifth Corps with sadness. This was in keeping with Gen. Griffin’s character. He was always ex- ceedingly punctilious in his relations with other officers, and never applied for any command or promotion, but always waited patiently for such things to come to him as the natural reward of duty well done. I do not suppose that he feared that Gen. Humphreys would misconstrue his attitude, but as Humphreys had long been Chief of Staff of the Army of the Potomac, and his opinions were held in great respect by the other officers, I presume Gen. Griffin sent that note as a mild form of expressing his disapproval of the relief of Warren.

p. 358: Gen. Warren was always popular with his troops and, so far as I know, with the officers who served under his command. He was a man of unflinching personal courage, faultless manners and unvarying equanimity. Of unusual politeness at all times, he became a veritable Chesterfield under fire. But he was not calculated, either by nature or by training, to get along with Gen. Sheridan, particularly in such a rough- and-tumble campaign as this was. Gen. Griffin made no comment on the relief of Warren, except to notify Gen. Bartlett that the command of the First Division would now devolve upon him, and took no action that night except to send the note to Gen. Humphreys, as before described. Gen. Griffin never said a word on the subject that could be construed into a per- sonal criticism. The most he would say was that, as Warren’s successor, he, of all men, must be silent.

p. 361 Appomattox Campaign :”The fatigues and privations were terrible, and nothing could have made me sustain them except the faculty that Griffin had of making men under his command perform prodigies.” V & XIV Corps under Griffin and Gibbon became foot cavalry” outrunning the telegraph service; p. 362 also difficulty of dealing with Crawford (pedantic about messages back and forth)

p. 365: All the infantry appeared to be in good heart, and as I rode through their bivouacs that night delivering messages to the division commanders I could not see that they were the least bit “done up,” as the English say, by the unheard of forced marching they had done. I cannot begin to find words to express the admiration, nay, the homage I felt for those heroic “dough boys,” who had footed it that day 35 miles in 10 hours, and who were now, at night- fall, gathering around fires of rails and limbs of trees boiling coffee in their tin cups, roasting pieces of salt pork on the ends of sticks or ramrods, their caps set on the backs of their heads, their pantaloons legs tucked in their boots, or more often into their old gray army socks— for many of the in- fantry wore shoes instead of boots — all soiled with mud and battered, but “fat, ragged and sassy.”

Ah well, it was only once in a lifetime—and comparatively few lifetimes at that — when one could see in flesh and blood and nerve and pluck and manhood that immortal old Fifth Corps on its way to Appomattox! On its way, keeping step and step with Sheridan’s cavalry, to get across the path of Lee’s army! During these terrible forced marches of the Fifth Corps Gen. Griffin’s wonderful power in dealing with soldiers, and his marvellous tact in cheering men on to incredible exertions, became mani- fest. If that noble man had a fault, it was his apparent incapacity to un- derstand that there was a limit to human endurance. In those marches we would be riding along the flank of the column, and the General would see a dozen or so of stragglers by the side of the road. He would then rein up his horse and call out to them :

“Hello, there! What is the matter with you fellows?”

“Clean tuckered out, General ; can’t march another step.”

“Look here, boys,” the General would reply, “don’t you know that we have got old Lee on the run, and our corps and the cavalry are trying to head him off? If he escapes from us old Sherman and his bummers will catch him and get all the glory, and we won’t have anything to show for our four years’ fighting ! Try it once more! Get up and pull out and re- join your commands. Don’t flicker this way at the last moment !” [366]

Then you would see those old fellows straighten up and pull them- selves together and shoulder their muskets, and they would look at one another and say :

“By —, boys, that’s so. The General is right. It will never do to let ‘Old Billy’ and his bummers catch Lee’s army. They are our meat, and we must have them ourselves !”.

Then they would begin tramping through the mud again, and Griffin would ride on to find some other squad of stragglers, and go through the same sermon over again. It made no difference how tired or faint or sore an Army of the Potomac man might be, he couldn’t endure the thought of letting Lee’s army get away, so that those Western fellows would catch him and get the glory of winding the thing up. When I was riding along with the escort I used to wish that I could dismount and give up my horse to every one of those poor, exhausted, but brave and determined infantry comrades, who were actually “falling by the wayside,” but who, when their pride was stirred by the thought that Sherman’s army might usurp the fruits of their toils and sufferings of four long years, took a new lease of life and strength and staggered on once more toward Appomattox and the end ! No one who did not see them can form the faintest idea of what they did and dared and suffered! And Gen. Griffin was a whole Provost guard all by himself.

At daybreak April 7, or a little before, Gen. Sheridan, who was then at Prince Edward Courthouse with Merritt’s Cavalry Division, sent his brother, Col. Mike Sheridan — who, by the way, rode nearly all night – to tell Griffin to move at once to Prince Edward Courthouse and there await further orders. I always had a fancy for Col. Mike Sheridan. He seemed to be the perfection of the rough-and-ready “Irish trooper,” always on hand, jolly, tireless, reckless ; in short, a born soldier. His ways were somewhat rough and his language sometimes more forcible than polite, but everybody noticed that Col. Mike always “got there, and everybody liked him. When he reached Griffin that morning he was covered with mud from head to foot, dressed in the uniform of a private cavalryman, with no insignia of his rank except his Captain’s bars on the collar of his jacket (he was only a Captain in the Regular Army, though a volunteer Colonel, and he always wore the marks of his Regular rank). The gallant Colonel was in need of “refreshments,” which it afforded me great pleasure to find for him.

The march from Ligonton to Prince Edward was about 28 or 30 miles, and we made it in about eight hours, halting along the Prospect Road, with Corps headquarters near the old College (Hampden-Sydney), just before dark. On arriving at Prince Edward Gen. Griffin had received information on his own account, which satisfied him that Lee was moving by the river roads toward Appomattox, and consequently the Fifth Corps at Prince Edward was a little too far south to be within striking distance in the coup de grace, which evidently must happen in a few days, or even hours. Griffin’s whole idea was that the old Fifth Corps must be in at the death. [367] Just at this time he received information that Gen. Gibbon, with two divisions of the Twenty-fourth Corps and two brigades of the Twenty-fifth, the whole forming a column under Gen. Ord, had preceded him, moving, as they did, by a shorter route from Petersburg, and that they would camp that night at Prospect Station, on the South Side Railroad, which was per- haps five miles northwest from the position where our corps halted. Gen. Gibbon had also sent a personal message to Griffin, stating that his com- mand would move before daylight on the 8th toward Appomattox Station, distant about 38 or 40 miles, and suggesting that his information was that if they could reach that point by the morning of the 9th they would get across Lee’s pathway, and therefore wind up the whole business.”

p. 377 “But if Elder’s Battery did fire the last cannon shot in action, Gen. Griffin and his staff, without doubt, got the benefit of the last musket shot from the enemy. About half way between the Trent House and the village there was a small building, which had been used as a blacksmith shop. As soon as the flag of truce appeared the General, accompanied by Col. Fred Locke, Maj. George B. Halstead, Capt. Schermerhorn and several Orderlies, rode out in front of the left of Chamberlain’s skirmish line, and had got a little beyond this shop, when about a dozen shots were fired from the grove on the right, just across Plain Run from the Sears House, distant from [378] he group about 60 or 70 rods. The balls zipped close, and Gen. Griffin said, “the — — — do they mean to murder us after they have sur- rendered?” He then proposed to go over to Pearson’s position and, as he expressed it, “turn the Old Third (Bartlett’s old Brigade) loose for a few minutes!” But before he could execute this purpose all firing ceased, and the General and his staff proceeded up the road from the blacksmith shop to the village, where Gen. Grant was just arriving.’

Posted in 189NY, Andrew Humphreys, Appomattox Campaign, artillery tactics, Bethesda Church, Charles Mink, Charles Phillips, David Russell, Edgar Gregory, Five Forks, Fred Locke, George Halstead, George Winslow, Gouverneur Warren, Gregpru, Harry Heth, Jacob Sweitzer, James Gwynne, James Stewart, John GIbbon, Joseph Bartlett, Joshua L. Chamberlain, Lester Richardson, Martin, Michael Sheridan, Orlando Willcox, Phil Sheridan, Phillips, Roman Ayres, Samuel Crawford, Sprigg Carroll, Wilderness | Leave a reply

No comments:

Post a Comment