Chancellorsville – division withdrawn to rifle pits near Chancellorsville House

p. 174 “Both Generals Griffin and Barnes were much chagrined at the peremptory order to stop. They made earnest appeals for the revocation of the directions, entered potent objections against their enforcement. From those who were in position to overhear the loud and angered tones of the conversation, it was reported that some hot, plain, determined words were spoken. General Griffin, filled with soldierly enthusiasm and just confident of his ability to take and hold the eminence, offered to surrender his commission if the attempt should prove a failure.”

p. 183 “General Griffin, an officer of unquestioned skill and untiring energy, beside the implicit confidence had the unbounded respect of every soldier in his division. His presence was assuring, and demonstrations were only restrained by the necessity for perfect quiet.”

p. 187: “The attack of the Confederates was so fierce and persistent that General Meade ordered General Griffin to put in his division. He asked permission to use the artillery then concentrating in the vicinity, saying ‘I’ll make them think hell isn’t half a mile off.’ Permission being granted, he ordered the gunners to double-shot their pieces, let the enemy approach to within fifty yards, ‘and then roll them along the ground like this,’ stooping in imitation of a bowler.”

p. 211 Spring 1863: “Dress-parade was in progress on a genial afternoon, and General Griffin's presence had stiffened the men to their best endeavors. The adjutant was peculiarly happy, his natty jacket, well-polished top-boots outside his pants, and his neat- fitting corduroys setting off his shape immensely. But it was not uniform. He had reached the " Sir, the parade is formed," when the general, who had kept his eye upon him alone, could remain silent no longer. "No, it is not, sir!" said he, address- ing the adjutant, "nor will it be until you return from your quarters clothed in the uniform of your rank; and, recollect, sir, with your pants outside of your boots." And then turning to the colonel, " I had hoped, sir, this would have received attention before I was compelled to notice it. You will bring your command to an order and await the adjutant's return."

The adjutant, meekly submissive, shortly appeared properly clothed and the ceremony was concluded. His subsequent orders lacked much of the snap with which he opened.

At other times a disposition to be unduly careless met with like reproof. General Griffin, during the hour for company drills, riding through the division to observe the regard paid to this requirement, happened upon a captain of repute, who wore a brown knit jacket instead of an officer's coat. The captain continued to manoeuvre his company, with that special care and little self-importance always assumed when in the presence of superiors. The general interrupted him several times, address- ing him as sergeant. The captain resented the application of the title and was at some pains to repeatedly announce his rank. The general was equally firm in his insistence upon the desig- nation he had first used, and ultimately explained he could recognize no commissioned officer in such an unsightly garb discharging the duties of his office. He ordered the captain to repair to his quarters and change his coat, and that [212] he would take charge of the company. He drilled it for some time and when the captain returned in his uniform, addressing him by his title, administering some wholesome advice upon the subject of dress, dignity, and use of the insignia of rank, directed him to continue the exercises."

p. 270: Gettysburg – Barnes “just deserved the consideration shown him by General Griffin, who arrived amid the heat of the contest and declined to assumed command until the battle was over. Griffin considerately remarked: ‘To you, General Barnes, belongs the honor of the field; you began the battle with the division, and shall fight it to the end.'"

p. 285 Incident at Lovettsville, VA July 17, 1863: “Moving at four in the afternoon to Berlin, and crossing the Potomac on pontoons laid at that point at 5:50, the regiment was again in old Virginia, and at 6:45 in camp at Lovettsville.....Some venomous spirit prompted retaliatory measure for wrongs done in Pennsylvania. Threats were made to destroy the village. General Griffin checked the affair in its incipiency, preventing a disgraceful scene of sack and pillage.”

p. 300 Execution of five deserters August 26, 1863: “General Griffin, who, annoyed from the beginning with unnecessary delays, had anxiously noted the waning hours, observed that but fifteen minutes were left for the completion of what remained to be done. In loud tones, his shrill, penetrating voice breaking the silence, he called to Captain Orne: ‘Shoot those men, or after ten minutes it will be murder. Shoot them at once.!’”

p. 303: “General Griffin had a mare, noted for its speed, of superior build and excellent carriage. There were often appreciative gatherings at his headquarters, when he was tempted by repeated challenges to test the metal of his splendid animal. Other steeds were of equal reputation, however, and regardless of the distinguished rank of the owner of this noted war-horse, not infrequently outstipped in the strife.”

p. 319 incident near Brandy Station October 11, 1863:

“Over the plain in front there were repeated charges and countercharges, with varied success as the one or the other side was in heaviest numbers. Presently the enemy appeared in considerable strength, bearing down hard upon our severely pressed horse. General Griffin, standing beside an idle battery unlimbered and "in action front," evidently concluded that the best way to re- lieve this pressure on the discomfited horse was to try some effective work with the guns. He stood in their midst and personally directed the fire. The first shot was too high, knocking off the branches of timber in the woods in front of which stood a large body of the enemy's cavalry. This practice did not suit him, and he directed the artillerymen to depress their pieces, remarking with considerable emphasis, as he had done once before, 'You are firing too high; just roll the shot along the ground like a ten-pin ball and knock their d—n trotters from under them,' practically illustrating his instructions by stooping and trundling his hand and running smartly as if in the act of bowling. Better work followed, and after several discharges the enemy disappeared entirely and the cav airy, infantry, artillery and trains continued the march without further interruption to the Rappahannock.”

p. 322 October 13, 1863: “General Griffin evidently anticipated battle, as he directed the release of private Thomas Sands, of Company F, who was under arrest awaiting execution, and ordered him to be equipped and returned to the ranks ready for the coming engagement.”

p. 324. As an illustration of the great confidence that the men had in the courage and generalship of General Griffin, who had recently returned to the division after a short absence, it may be mentioned that the officers could do nothing better to reassure the troops than to say: ‘Men, General Griffin is in command.’”

p. 432 withdrawal from Spotsylvania, pickets insulted by Confederates May 21, 1864: “But General Griffin, seated composedly on his horse, as our men reached their cover, encouraged them with the assurance that their run was all part of the game, and that others were at hand to re- [433] ent the insult. And so they were, for when all the pickets were safely stowed away, a counter-charge gathered in a goodly number of the enemy, who in the wild excitement of success had ventured beyond the bounds of prudence.”

p. 505. Maj. GC Hopper 1MI, report of encounter with CG August 20, 1864 at Weldon RR. “I received a summons to report to General Charles Griffin, our division commander. ‘He said to me: “Major, we will probably be attacked early [506] to-morrow morning, and nothing so discourages an enemy as to find a determined resistance on the picket line. Your position is a long way in front, and if you give them a good fight it will greatly weaken them by the time they reach the breastworks.”

p. 511. Sept. 1864: “Horse-racing again found a place among the amusements. A level stretch of the Halifax Road furnished the track, and the first race between General Griffin’s gray mare and the commissary of musters’ gray stallion resulted in the defeat of the general’s animal.”

p. 513: movements 9/30/64: “Here under the personal direction of General Griffin skirmishers were thrown out. Of the detail was one officer and twenty men from the 118th. They had not gone far when they developed the enemy’s pickets behind light works thrown up along the road in front of Poplar Grove Church. After some sharp firing the enemy fell back to his main line. In this skirmish, gallantly pressing [514] forward Lieutenant Conahay was killed. General Griffin was beside him when he fell.”

p. 519 more combat on 9/30/64: “And then amid it all General Griffin came along, resolute, heroic, impressive, with words and comforting promises of help. The wavering lines stiffened; strong men were strengthened and the weak made strong. From now it was his fight, and his presence in inspiring the men was almost equal to the promised support of his batteries.”

Griffin absent on leave from Oct. 19, 1864 to about Oct. 26, 1864

pp. 568-9: Griffin’s managing action at Hatcher’s Run - March 1865

p. 639. Wrt Charles P. Herring, Col 118PA: Griffin wrote “Gallant and ever reliable as an officer, he was humane and considerate towards those under him, always being solicitous for their welfare. On the field of battle, or in camp, his manly bearing won for him the friendship for all. His record is one that he not only should feel proud of, but his State should prize as belonging to one of her sons.”

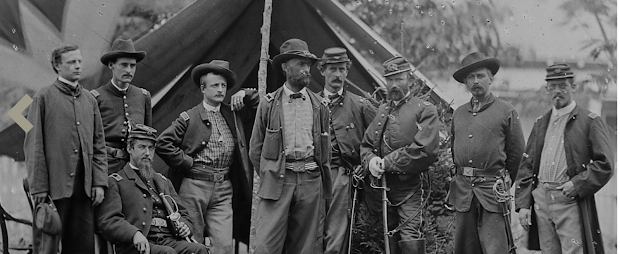

p. 648 Major-General Charles Griffin was the popular and brilliant commander of the 1st Division of the 5th Corps until the removal of General Warren, when he was placed in command of the corps. No officer in the army could have been more dearly beloved by his men than General Griffin. He was a tall, slim, well-built man, and rode very erect, with his head well thrown back, and with his long sharp chin well advanced to the front. In the field he paid little attention to dress, and his rank was indicated principally by the gold cord around his felt hat; his face was shaved smooth, while his lip was adorned with a heavy moustache. General Griffin was one of the finest-looking officers in the army. Always kind, pleasant and cheerful, his presence even in defeat always seemed like a sun- beam. He was as fearless as a tiger, and would lead his division anywhere. He had formerly been an artillery officer and conse- quently had great faith in that branch of the service. We all mourned when his death was announced, several years after the close of the war. He died of yellow fever in New Orleans. There were but few officers in the Union army more worthy of praise than was General Charles Griffin.

Source: History of the Corn Exchange Regiment 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers – Survivor’s Association (Philadelphia 1888) https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hx4u2q

No comments:

Post a Comment