Thirty-Second Regiment Massachusetts Infantry: whence it came, where it went, what it saw; and what it did. Francis J. Parker (Boston 1880)

p. 46. Through all this we succeeded in finding General Porter's headquarters, and by his direction were guided to a position a mile or more distant, and placed in line of battle with other troops in face of a thick wood, and then learned that we were assigned to the brigade of General Charles Griffin, division of General Morell, in Fitz John Porter's, afterward known as the Fifth army corps.

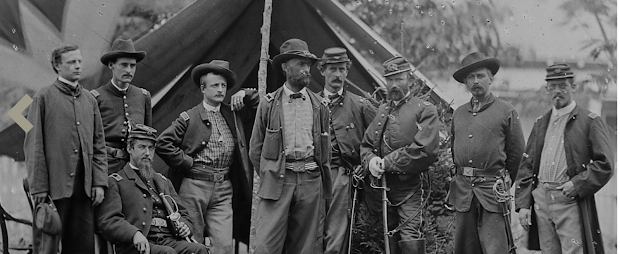

As soon as we were fairly in position our Colonel sought for the brigadier. The result was not exactly what his fancy may have painted. On a small heap of tolerably clean straw he found three or four officers stretched at full length, not very clean in appearance and evidently well nigh exhausted in condition. One of them, rather more piratical look- ing than the others, owned that he was General Griffin, and endeavored to exhibit some interest in the addition to his command, but it was very reluc-[47] tantly that he acceeded to the request that he would show himself to the Regiment, in order that they might be able to recognize their brigade commander.

After a time however, the General mounted and rode to the head of our column of divisions. The Colonel ordered "attention” and the proper salute, and said: "Men, I want you to know and remember General Griffin, our Brigadier General.” Griffin's address was perhaps the most elaborate he had ever made in public. "We've had a tough time men, and it is not over yet, but we have whaled them every time and can whale them again.”

Our men, too well disciplined to cheer in the ranks, received the introduction and the speech, so far as was observed, in soldierly silence, but months afterward the General told that he heard a response from one man in the ranks who said, “Good God l is that fellow a general.” We all came to know him pretty well in time, and to like him too, and some of us to mourn deeply when he died of the ſever in Texas, after the surrender.

p. 113 After Antietam.

“One of our men, returning from a private foraging expedition laden with a heavy leg of beef, was cap- tured by the provost guard, and, by order of General Griffin, was kept all day “walking post,” with the beef on his shoulder, in front of the head- quarters' tents. As the General passed his beat he would occasionally entertain him with some question as to the price of beef, or the state of the provision trade, and at retreat the man, minus his beef, was sent down to his regiment “for proper punishment,” which his commanding officer concluded that he had already received.

Yet another soldier was sent to our headquarters by the Colonel of the Ninth Massachusetts, with the statement that he had been arrested for maraud- ing. Upon cross-examination of the culprit it [114]. appeared that he had been captured with a quarter of veal in his possession by the provost guard of the Ninth Regiment. A regimental provost guard was a novelty in the army, but when, on further questioning, it appeared that the offending soldier had been compelled to leave the veal at Colonel Guiney's quarters, the advantage of such an organization in hungry times to the headquarters' mess was apparent, and our Colonel at once ordered a provost guard to be detailed from the Thirty-second, with orders to capture marauders and turn over their ill- gotten plunder to his cook. Unhappily, within the next twenty-four hours, some high General, whose larder was growing lean, forbade regimental pro- vost guards in general orders.

It was during our stay at Warrenton that General Griffin requested the attendance of Colonel Parker and told him, not as an official communication, but for his personal information, that three officers of the Thirty-second had, during the previous night, taken and killed a sheep, the property of a farmer near by. Of course the Colonel expressed his re- gret at the occurrence, but he represented to the General that, inasmuch as the officers of our regiment were not generally men of abundant means, and inasmuch as they had received no pay from their Government for several months, and inas- much as it was forbidden them to obtain food by taking it either from the rations of their men or the property of the enemy, he (the Colonel) would be glad to know how officers were to live? The [115] General, utterly astonished at the state of affairs thus disclosed, asked in return for some suggestion to relieve the difficulty. The suggestion made that officers should be allowed to buy from the commissaries on credit, was, at the request of General Griffin, embodied in a formal written communication to him, and by an order the next day from the headquarters of the army, it became a standing regulation until the end of the war.

p. 249: “That night, by order of General Sheridan, General Warren was relieved, and General Griffin (our “Old Griff”) was placed in command of the 5th Corps. It is not easy to see what default in duty could have been ascribed to Warren, and it is prob- able that the real explanation of the change was merely Sheridan's preference or partiality for Griffin, who was patterned more after Sheridan's taste.”

No comments:

Post a Comment