[p. 329]

#1353..(Born O.).......CHARLES GRIFFIN...... (Apd 0.). .WEST POINT CLASS ’47: RANK: 23

Military History. — Cadet at the Military Academy, July 1, 1843, to July 1, 1847, when he was graduated and promoted in the Army to

Bvt. SECOND LIEUT., 4TH ARTILLERY, JULY 1, 1847.

Served : in the War with Mexico, 1847-48, on March to Puebla ; on

(SECOND LIEUT., 2D ARTILLERY, Oct. 12, 1847)

sick leave of absence, 1848 ; in garrison at Tampa Bay, Fla., 1848, - and Ft. Monroe, Va., 1848-49; on frontier duty, at Santa Fé, N. M., 1849,–

(First LIEUT., 2D ARTILLERY, JUNE 30, 1849)

Scouting, 1849, Santa Fé, N. M., 1849–50, Albiquia, N. M., 1850,Santa Fe, N. M., 1850–51, Expedition against Navajo Indians, 1851, and Ft. Defiance, N. M., 1851-52, 1853–54 ; in garrison at Ft. McHenry, Md., 1854–57 ; conducting recruits from Carlisle, Pa., to Ft. Leavenworth, Kan., 1857; in garrison at Ft. Independence, Mas., 1857 ; on frontier duty at Ft. Snelling, Min., 1857, — Ft. Leavenworth, Kan., 1857, escorting Governor to New Mexico, 1857–58, — Ft. Leavenworth, Kan., 1858, – and Ft. Riley, Kan., 1858–59 ; on leave of absence, 1859–60 ; and at the Military Academy, as Asst. Instructor of Artillery, Sep. 11, 1860, to Jan. 7, 1861.

Served during the Rebellion of the Seceding States, 1861–66; in command of Battery at Washington, D. C., Jan. 31 to July, 1861, — in the

(CAPTAIN, 2D ARTILLERY, APR. 25, 1861)

Manassas Campaign of July, 1861, being engaged in the Battle of Bull

(TRANSFERRED TO 5TH ARTILLERY, MAY 14, 1861)

Run, July 21, 1861, - and in the Defenses of Washington, D. C., July,

(Bvt. MAJOR, JULY 21, 1861, FOR GALLANT AND MERITORIOUS SERVICES AT THE BATTLE OF BULL Run, VA.)

1861, to Mar., 1862 ; in the Virginia Peninsular Campaign, commanding [p. 330] Battery, Mar. to June, and Brigade of 5th Corps, June to Aug., 1862

(Brig.-GENERAL, U. S. VOLUNTEERS, JUNE 9, 1862)

(Army of the Potomac), being engaged in the Siege of Yorktown, Apr. 5 to May 4, 1862, — Action and Capture of Hanover C. H., May 27, 1862, Battle of Mechanicsville, June 26, 1862, — Battle of Gaines's Mill, June 27, 1862, — Battle of Malvern Hill, July 1, 1862, — and Action of Malvern Hill, Aug. 5, 1862 ; in command of 2d Brigade, 5th Corps (Army of the Potomac), in the Northern Virginia Campaign, Ang.-Sep., 1862, being engaged in the Battle of Manassas, Aug: 30, 1862 ; in the Maryland Campaign (Army of the Potomac), Sep. to Nov., 1862, being engaged in the Battle of Antietam, Sep. 17, 1862, Skirmish at Shepardstown, Sep. 19, 1862, - and March to Falmouth, Va., Nov., 1862 ; in command of 1st Division, 5th Corps (Army of the Potomac), in the Rappahannock Campaign, Dec., 1862, to May, 1863, being engaged in the Battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862, and Battle of Chancellorsville, May 2-4, 1863 ; on sick leave of absence, May 15 to July 2, 1863 ; in command of 1st Division, 5th Corps (Amy of the Potomac), July 3 to Oct. 24, 1863 ; in the Pennsylvania Campaign, and in Central Virginia, being engaged in the Battle of Gettysburg, July 3, 1863, — and Several Skirmishes ; on sick leave of absence, Oct. 24 to Nov. 3, 1863 ; on Court-martial duty, Nov. 3, 1863, to Apr. 3, 1864; in command of 1st Division, 5th Corps (Army of the Potomac), Apr. 3, 1864, to Apr. 1, 1865, and of 5th Army Corps, Apr. 1, 1865, in the Richmond Campaign, being engaged in the Battle of the Wilderness, May 5–6, 1864, Battles about Spottsylvania C. H.,

(Bvt. LIEUT.-COLONEL, MAY 6, 1861, FOR GALLANT AND MERITORIOUS SERVICES AT THE BATTLE OF THE WILDERNESS, VA.)

May 9–20, 1861, — Battle of Jericho Ford, May 23, 1864, Battle of Bethesda Church, June 1-4, 1861, Assault of Petersburg, June 18, 1864,Siege of Petersburg, June 18 to July 20, 1861, and Aug. 9, 1864, to Mar. 29,

(Bvt. MAJOR-GENERAL, U. S. VOLUNTEERS, Aug. 1, 1864, For CONSPICUOUS GALLANTRY IN THE BATTLES OF THE WILDERNESS, SPOTTSYLVANIA C. H., JERICHO Mills, BETHESDA CHURCH, PETERSBURG, AND GLOBE TAVERN (WELDON RAILROAD), AND FOR FAITHFUL SERVICES IN THE CAMPAIGN)

1865, - Battles on the Weldon Railroad, Aug. 18-21, 1864, — Action of

(Bvt. COLONEL, Aug. 18, 1864, FOR GALLANT AND MERITORIOUS SERVICES IN THE BATTLE ON THE WELDON RAILROAD, VA.)

Peebles' Farm, Sep. 30, 1864, — Movement to Hatcher's Run, Oct. 27-28, 1864, - Destruction of Weldon Railroad to Meherrin River, Dec. 7-10, 1864, - Action of Hatcher's Run, Feb. 7–8, 1865, – Actions and Move

(Bvt. Brig.-GENERAL, U. S. ARMY, Mar. 13, 1865, FOR GALLANT AND MERITORIOUS SERVICES AT THE BATTLE OF FIVE FORKS, VA.)

(Bvt. MAJ.-GENERAL, U. S. ARMY, MAR. 13, 1865, FOR GALLANT AND MERITORIOUS SERVICES IN THE FIELD DURING THE REBELLION)

ment to White Oak Ridge, Mar. 29–31, 1865, — Battle of Five Forks, Apr. 1, 1865,- Pursuit of Rebel Army under General Lee, Apr. 3-9,

(MAJOR-GENERAL, U. S. VOLUNTEERS, APR. 2, 1865)

1865, — Action of Appomattox C. H., Apr. 9, 1865, — and Capitulation of Appomattox C. H., Apr. 9, 1865, he being one of the Commissioners to carry into effect the stipulations for the surrender; in command of 5th Army Corps till June 28, 1865, at Nottaway C. H , guarding Petersburg Railroad, Apr. 20 to May 1, 1865, March to Washington, May 1-23, 1865, — and near Washington, D. C., May 23 to June 28, 1865; in com-[p. 331] mand of the District of Maine, Aug. 10 to Dec. 28, 1865; and awaiting orders, Dec. 25, 1865, to Mar. 10, 1866.

MUSTERED OUT OF VOLUNTEER SERVICE, Jan. 15, 1866.

Served : as Member of Board to determine the kind of small-arms for the service of the Army, 1866 ; awaiting orders, to Nov. 15, 1866; in

(COLONEL, 35TH INFANTRY, JULY 28, 1866)

command of District of Texas, Nov. 28, 1866, to Sep. 5, 1867, — and temporarily of Fifth Military District (Louisiana and Texas), Sep. 5–15, 1867.

DIED, SEP. 15, 1867, AT GALVESTON, Tex.: AGED 41.

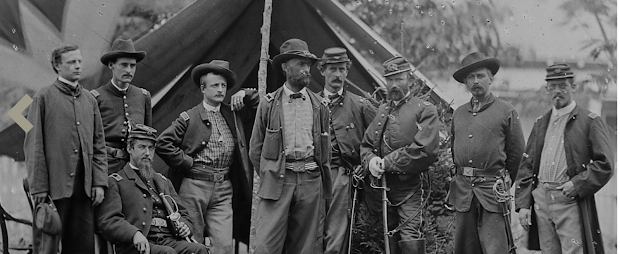

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH.

Bvt. MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES GRIFFIN was born, January, 1826, in Licking County, Ohio. From Kenyon College, Ohio, he entered the Military Academy, from which he was graduated July 1, 1847; was promoted to the Artillery, and was immediately ordered to Mexico, taking command of a company on the march of General Patterson's column from Vera Cruz to Puebla. From the termination of this war till the outbreak of the Rebellion he was mostly engaged on frontier duty.

In command of the “West Point Battery,” he won the brevet of Major in the Battle of Bull Run ; was appointed, June 9, 1862, Brigadier-General, U. S. Volunteers ; and was distinguished in the Virginia Peninsular Campaign. After joining the Army of Virginia, he was engaged in the Battle of Manassas, and was charged in the commanding general's report with making unseemly remarks, and refraining from taking part in the conflict, for which he was arrested for trial, but soon released. In command of his brigade he served through the Maryland Campaign, when he was placed at the head of a division, with which he fought through the Rappahannock, Pennsylvania, and Richmond Campaigns. At the close of these three years of toilsome marches and bloody battles, he was put at Five Forks in command of the Fifth Corps, and by order of General Grant received the arms and colors of the Confederate army surrendered at Appomattox C. H. For his gallant and meritorious services during the Rebellion he was brevetted from Major to Major-General in the Regular Army, and promoted, Apr. 2, 1865, Major-General, U. S. Volunteers.

After becoming Colonel, July 29, 1866, of the 35th Infantry, he commanded the District of Texas, and, temporarily, the Fifth Military District (Louisiana and Texas), till his death, Sep. 15, 1867, at the early age of 41.

"General Griffin,” says his classmate, Col. John Hamilton, “although always glad to meet his friends, was somewhat reserved ; a little disposed to be cynical, and to depreciate in words that which he even respected in fact. He was punctilious, and quick to resent insult, fancied or real. Indeed, it might not be too strong to say that his nature was bellicose. Withal, he was a hearty liker, and would make sacrifice to help his fellow-man, but he was very severe on those who lost his esteem.

“As a soldier, nothing could keep him away from where he thought duty pointed, regardless of any other claim; and the sickness that called him hence was a sacrifice to his ideas of duty, which, had he been less conscientious, could readily have been evaded with no dishonor.

[CLASS OF 47 INCLUDES ORLANDO B WILLCOX (8); JAMES B FRY (14); AP HILL (15); AMBROSE BURNSIDE (18); JOHN GIBBON (20); ROMEYN AYRES (22); HENRY HETH (38)]

Source: Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, NY by Bvt Maj-Gen George W. Cullum, 3rd ed. Vol. II (New York 1891)

PROMOTIONS:

United States. Congress. Senate. (1828). Journal of the executive proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America. Washington: Printed by order of the Senate of the United States.

p. 100 promotions - Second Regiment of Artillery

Second Lieutenant Charles Griffin to be first lieutenant, June 30, 1849, vice Sears, resigned.

United States. Congress. Senate. (1828). Journal of the executive proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America. Washington: Printed by order of the Senate of the United States

p. 451 Promotions: Second Regiment of Artillery

First Lieutenant Charles Griffin to be captain, April 25, 1861, vice Elzey resigned.

p. 507 Captain, Fifth Regiment of Artillery 4/25/61